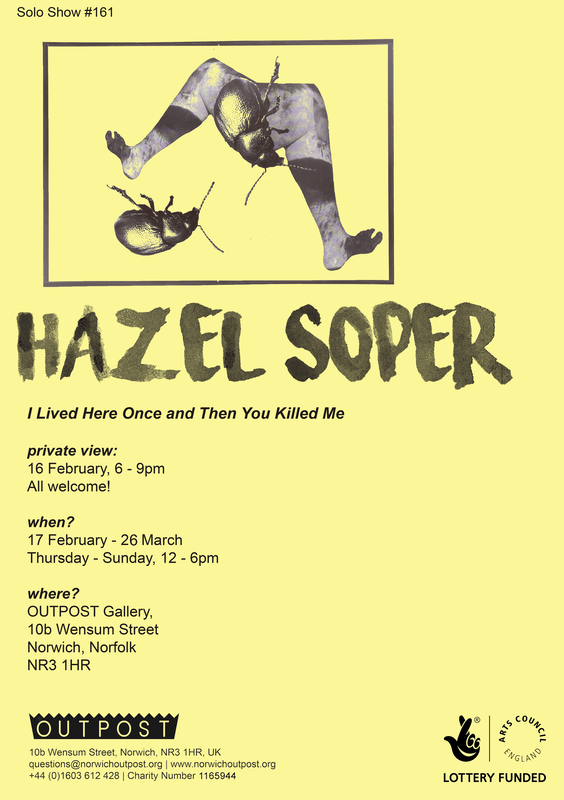

I Lived Here Once and then You Killed Me, OUTPOST Gallery, 2023

Branches, copper sculpture, thread, Mobile phone with video work, cable ties, solar charger, Neon artwork, steel chain, log, ceramic sculptures, laser cut plywood, soil, soft sculpture seating, zoom player with audio piece, central video and audio on screen.

Interview between OUTPOST's Dan Randal and Hazel Soper

DR: Your exhibition takes a look at the Norfolk Folklore story of St Mary’s Church and The Witch’s Wooden Leg, what drew you to this story?

HS: I really like this story as a kind of archetype of the treatment of women; a woman was suspected of ‘witchcraft’ (but really this could be anything that transgresses the patriarchal norms) and was taken by the Somerton villagers, buried inside a church and killed. Before dying, she bewitched her wooden leg to grow up into a tree that eventually broke the church apart- destroying this centre of the community and symbol of the control and values that repressed her. The story is very linked to the power of nature, and how women and nature are often seen as unruly, irrational with the need to be controlled, tamed or extinguished. In a time of both climate crisis, and where the rights of women (and human rights in general) are being repealed, for instance Roe vs Wade in the US, I think it’s particularly important that we reflect and consider our cultural values, and the violence these can lead to.

DR: Does folklore play a larger role in influencing your work?

HS: It plays a big role in my work, and I think the choice of installation as a medium. I want to create an immersive experience of sensationalised sinister femininity that encompasses a viewer. I think artwork is more exciting, accessible, engaging and inspiring when magic is involved. Like fairy stories and folklore, I love art for the way it can make everyday life extraordinary, and bring some joy into the world that wasn’t there before. Particularly right now when things are so difficult for so many, I think imagination is imperative to create a different, alternative, inclusive future for us all. Folklore and stories also reflect our beliefs as a society, and which roles we are expected to play. As an angry feminist, I think it’s important to revisit and reexamine which roles we are cast into and why- and if we want to be part of someone else’s story at all.

DR: Video, audio, textiles, natural materials, and lighting are all key elements in the exhibition, could you tell us a bit about the relationship between the media and the themes of the show?

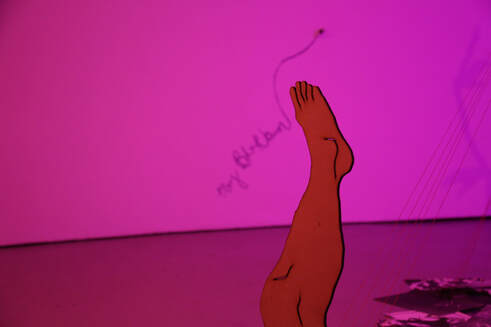

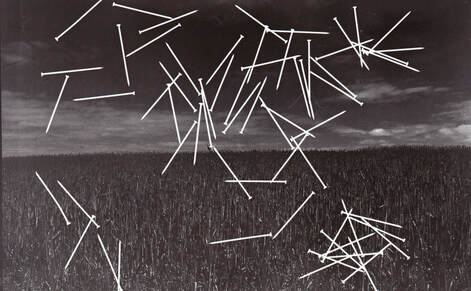

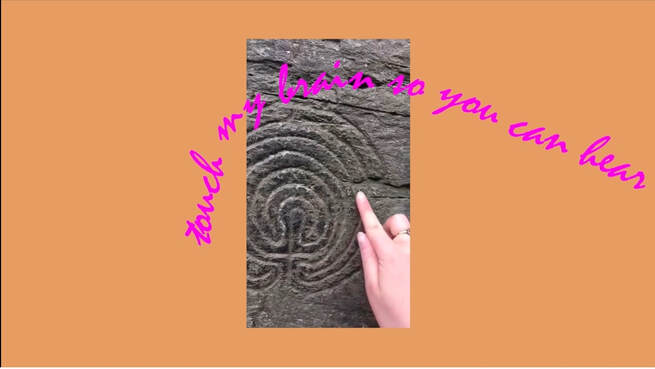

HS: I think that the use of textiles and natural materials hark back to traditions of female labour, sewing and craft. My grandmother was a tailor and taught me to sew when I was very young, so I’ve always been very interested in this practical way of working, and it’s something very personal to me. Textiles and women’s work are often associated with the home, and a mother’s care and kindness. I think it’s really important that we collectively celebrate and accentuate these qualities, to look after each other. With this work in particular, I imagined the home that the Somerton Witch would create for herself after she was buried, grown out of her body under the soil. The squishy, textile elements of her thighs and belly, the wooden legs, the glowing, ecstatic brain alive with her thoughts and soul, chained to the ground where she has been made to stay. With the metal elements I wanted to create a harshness within the work- emulating the experiences of danger and defence that are part of anyone who identifies as a woman, or differs from a patriarchal standard. I often incorporate tech elements into my work- I think the more we understand that our modern lives and natural environments are linked and co-dependent the better, and I also want to acknowledge the real world context of the piece outside of the gallery space. Phones, surveillance, screens and music are all such a big part of our lives, so not including them within the gallery to me seems disingenuous, and a way of projecting a romanticised view of the past.

DR: You feature throughout this exhibition, from the film to the snail/human hybrid, do you find that you play a role in your work and what that role might be?

HS: My work has some performative elements, and many of my body parts feature dismembered throughout the space. Again, this suggests the violence directed towards women, the lack of bodily autonomy but also acts as an expanded self portrait. I’ve wanted to highlight the experiences of a contemporary woman, but I don’t want to speak on anyone else’s behalf or appropriate anything. As we all know the media and now social media dictates the lens through which women are presented- to try and avoid adding to this problem I show myself through the lens in which I see myself, to only objectify my own life and body.

DR: Could you tell us about the title of the show?

HR: I Lived Here Once and then You Killed Me refers to both myself, having grown up in rural Norfolk, very near to the Somerton church, and also to the Witch herself. I wanted to be provocative with the title, so we can take a close, critical look at why women are being harmed, and indeed murdered as we speak. This isn’t a thing of the past or of fairy tales, it’s something that every woman walking home knows to be afraid of. To end on a less bleak note, I hope that this space can be a way of accepting these realities, whilst also creating a nurturing and delicious Witch’s house party for us to be kind to each other in.

DR: Your exhibition takes a look at the Norfolk Folklore story of St Mary’s Church and The Witch’s Wooden Leg, what drew you to this story?

HS: I really like this story as a kind of archetype of the treatment of women; a woman was suspected of ‘witchcraft’ (but really this could be anything that transgresses the patriarchal norms) and was taken by the Somerton villagers, buried inside a church and killed. Before dying, she bewitched her wooden leg to grow up into a tree that eventually broke the church apart- destroying this centre of the community and symbol of the control and values that repressed her. The story is very linked to the power of nature, and how women and nature are often seen as unruly, irrational with the need to be controlled, tamed or extinguished. In a time of both climate crisis, and where the rights of women (and human rights in general) are being repealed, for instance Roe vs Wade in the US, I think it’s particularly important that we reflect and consider our cultural values, and the violence these can lead to.

DR: Does folklore play a larger role in influencing your work?

HS: It plays a big role in my work, and I think the choice of installation as a medium. I want to create an immersive experience of sensationalised sinister femininity that encompasses a viewer. I think artwork is more exciting, accessible, engaging and inspiring when magic is involved. Like fairy stories and folklore, I love art for the way it can make everyday life extraordinary, and bring some joy into the world that wasn’t there before. Particularly right now when things are so difficult for so many, I think imagination is imperative to create a different, alternative, inclusive future for us all. Folklore and stories also reflect our beliefs as a society, and which roles we are expected to play. As an angry feminist, I think it’s important to revisit and reexamine which roles we are cast into and why- and if we want to be part of someone else’s story at all.

DR: Video, audio, textiles, natural materials, and lighting are all key elements in the exhibition, could you tell us a bit about the relationship between the media and the themes of the show?

HS: I think that the use of textiles and natural materials hark back to traditions of female labour, sewing and craft. My grandmother was a tailor and taught me to sew when I was very young, so I’ve always been very interested in this practical way of working, and it’s something very personal to me. Textiles and women’s work are often associated with the home, and a mother’s care and kindness. I think it’s really important that we collectively celebrate and accentuate these qualities, to look after each other. With this work in particular, I imagined the home that the Somerton Witch would create for herself after she was buried, grown out of her body under the soil. The squishy, textile elements of her thighs and belly, the wooden legs, the glowing, ecstatic brain alive with her thoughts and soul, chained to the ground where she has been made to stay. With the metal elements I wanted to create a harshness within the work- emulating the experiences of danger and defence that are part of anyone who identifies as a woman, or differs from a patriarchal standard. I often incorporate tech elements into my work- I think the more we understand that our modern lives and natural environments are linked and co-dependent the better, and I also want to acknowledge the real world context of the piece outside of the gallery space. Phones, surveillance, screens and music are all such a big part of our lives, so not including them within the gallery to me seems disingenuous, and a way of projecting a romanticised view of the past.

DR: You feature throughout this exhibition, from the film to the snail/human hybrid, do you find that you play a role in your work and what that role might be?

HS: My work has some performative elements, and many of my body parts feature dismembered throughout the space. Again, this suggests the violence directed towards women, the lack of bodily autonomy but also acts as an expanded self portrait. I’ve wanted to highlight the experiences of a contemporary woman, but I don’t want to speak on anyone else’s behalf or appropriate anything. As we all know the media and now social media dictates the lens through which women are presented- to try and avoid adding to this problem I show myself through the lens in which I see myself, to only objectify my own life and body.

DR: Could you tell us about the title of the show?

HR: I Lived Here Once and then You Killed Me refers to both myself, having grown up in rural Norfolk, very near to the Somerton church, and also to the Witch herself. I wanted to be provocative with the title, so we can take a close, critical look at why women are being harmed, and indeed murdered as we speak. This isn’t a thing of the past or of fairy tales, it’s something that every woman walking home knows to be afraid of. To end on a less bleak note, I hope that this space can be a way of accepting these realities, whilst also creating a nurturing and delicious Witch’s house party for us to be kind to each other in.